I had a conversation with someone recently. This person was concerned about the falling rates of marriage in the world and the rising rates of pre-marital live-in relationships. This simple correlation was the cause of much evil in the world. If only people lived traditionally: married, then moved in together, had a good set of kids, and then stayed together no matter what. Life would be much simpler.

I politely disagreed. While I had been raised religiously and understood the point of view, my reading on gender and the laws affecting women across the centuries has developed my views dramatically. My conversation partner has most likely only been exposed to a canon of literature written by men, who held a very limited set of views about women and what women ought to be allowed to do. That canon’s definition of women is fairly one-note: we want, even need, to submit to men. No surprise there, considering the authorship. That literary canon can be received as prescriptive, even prophetic, since some of the male authors may have been very influential, so that their ideas were taken as gospel. The power of those authors in religious and political spheres can make it very difficult for women readers to avoid that submission, especially as they balanced the needs of home and childcare.

I politely responded in the conversation. The literature about women and even by women is incredibly diverse. That is, the history of women’s literature changes what we know about women’s thoughts, desires, needs, fears, and movements because it more closely connects to the authentic experiences of women. This literature is fascinating, the opposite of what we have been taught, and most times, shows evidence that people in power have tried to suppress those direct lived experiences.

My conversation friend and I moved on to new waters, but the germ of the idea has been turning over in my mind since then. So, I decided to write about it.

In America in the twenty-first century, a woman’s goodness and social standing is still closely tied to her relationship status. Is she single? Dating? Married? Married with children? Divorced? Single Mother? These factors indicate whether the public ought to read her as valuable, broken, or “toxic.” Of course, these factors are built upon myths that have been perpetuated for centuries (by *cough cough* the patriarchy) that do not take into account the actual situation or any lack of social support. However, women still often feel the need to ascribe to these invisible gender roles.

For the following, I want to be clear that when I say women, I mean womxn (or AFAB, or Assigned Female At Birth). When I say men, I mean the patriarchy or the institutional powers that enforce oppressive gender roles (e.g. religion, the courts, the police, standards of dress, cultural memory, and even a woman’s own internalized misogyny).

Let’s start off with a premise: Women always had to get married in monogamous relationships, and that was a good thing.

Actually, the laws around marriage in Britain were changed in early medieval by Rome to fit into religious and political agendas. According to Henry Mayr-Harting’s The Coming of Christianity to Anglo-Saxon England, late antique and early medieval Old English culture did not disallow bigamy.[1] More significantly, according to Stephanie Hollis’ Anglo-Saxon Women and the Church: Sharing a Common Fate, Hollis relates that Pauline dictates and Christian canons at the Council at Hertford on marriage reconstructed the marriage contract from an agreement between two persons into a life-long hierarchical institution. Missionary reports from Rome on early England reported the loyal kinship or comradeship bonds for marriage, in which a common fate is shared through hardship as equals. The new laws forbade divorce except on the grounds of adultery, which the church restricted through penances and limitations on marriage. In general, the preservation of marriage was most important, even if a woman requested to dissolve her vow to enter a monastery.[2]

Hollis relates that Pauline dictates and Christian canons at the Council at Hertford on marriage reconstructed the marriage contract from an agreement between two persons into a life-long hierarchical institution.

That is to say, Mediterranean society did not give women a great deal of liberty, so following the Roman conquest and then the Christianization of England from 600 AD, Roman rules of marriage slowly became enforced in Britain. Men, particularly kings as example, were required to keep only one wife as queen. The second (or politically inconvenient) wife was often sent to a monastery to take up holy orders.[3] According to Hollis, these early divorcées could keep their property when they entered the church[4] (though the rules around property began to change). The imposition of Roman law on marriage was a way to enforce compliance on British genealogy, ancestry, and descendants. By asserting control over the marriage and birthing population, the Church would have control over the spiritual legitimacy of a nation by being able to control who was named into power by direct blood lineage. The previous Old English model appeared to allow women more agency, respect, and influence; the sexism displayed by early Roman sources is not as present in Old English sources until the later medieval period. In addition, the route to kingship could be chaotic: a king’s son had a good solid chance at being the next king, but sometimes the best warrior won. In short, while Christianization brought a level of peace to Britain, it standardized the island’s gender roles and deliberately silenced women.

Okay, so women didn’t always prefer monogamy. We have records for how women were being written about though? And how women were being spoken about? Yes, we do. Hang onto your seat.

The medieval conception of women allows us to consider gender in a new way. The medieval literary canon provides a large number of texts describing the behavior of married or clearly heterosexual women. Among these texts, romances describe how a woman becomes entangled with a lover (as in Morte D’Arthur, where Guinevere loves Sir Launcelot to a tragic end). Satiric texts such as Erasmus’ In Praise of Folly[5] describe the ways in which women were unsatisfactory lovers or wives, giving tacit justification to men to mistreat them through literary descriptions of acts.

In addition to fiction and poetry, religious texts provided conduct instructions or exempla (examples) about women. For example, St. Ælfric of Eynsham’s tenth century Lives of the Saints could have been read by communities of women as well as men. His graphic work describes how women saints like St. Agnes preferred a violent death to marriage if pursued against their vows; how even in the case of a fully Christian marriage like Julian and Basilissa’s, saints would prefer to remain chaste rather than consummate a marriage and defile themselves.[6] Ælfric was not by any means a feminist.

Ælfric argues from a place in which he believes that the sexual act is defiling.[7] While women very may well have had exposure to his works, his primary audience was most likely male. By Ælfric’s time, women would have been, in the words of Karma Lochrie, a “site of the taboo” where the church exerted particular control. According to medieval thought, women’s bodies were based on the anatomy of men though a woman’s parts were inferior. Though writing centuries later than Ælfric, authors like Bernard of Clairvaux and St. Augustine could disagree whether the body itself was evil, but they tended to agree that the flesh or the corrupting Will needed to be mastered. Women entered religious vocations as a weaker sex, and so they were usually considered to be temptresses and were the focus of much of the church’s need for control.[8] In literary works, then, women were re-imagined as the Will[9], which meant that they needed to be mastered and ruled over by the more rational and capable members, so that the whole unit (the house, the family, the marriage, the religious order) did not descend into sin. Since the Will was flesh and women tempted good men into darkness unless they were taught a better way (for example, Eve in the Garden of Eden), society was given a carte blanche to describe and control their bodies as needed.

Some texts were written by men for women. For example, The Katherine Group served as a set of devotional texts for women who were interested in taking a vow as a nun or even an anchorite. The Katherine Group included The Saints’ Lives, The Martyrdom of Saint Katherine, The Life and Passion of Saint Margaret, and The Life and Passion of Saint Julian, Hali Meithhad (Holy Maidenhood), and The Sawles Ward (Guardianship of the Soul). The Katherine Group is closely related to the Ancrene Wisse and the Wooing Group, which highlighted female spiritual experience. The lives of the saints in The Katherine Group (Katherine, Margaret, and Julian) describe how they debate philosophers and send demons (in the shape of a dragon!) back to hell, before the saints are martyred for their faith. The texts are exciting, engaging and often funny, and certainly inspiring.

According to the introduction to the Introduction to the Katherine Group provided by the TEAMS English Text Society, Hali Meithhad (Holy Maidenhood) praises the life of a virgin and bride of Christ. The author compares the preferable life of virginity, in which a woman is “married” to Christ, to secular marriage with an inferior human man, childbirth, and raising children, which could include abuse, illness, and grief. As the introduction makes clear, the content of the Hali Meithhad is drawn from the molestiae nuptiarum (tribulations of marriage) tradition, which began with the St. Paul. In the Hali Meithhad, the male author tries to re-imagine the trials of marriage from the female point of view, using that same literary convention.[10] The purpose of the Hali Meithhad was to assist and aid, and perhaps even to convince, women to take vows of celibacy.

The Hali Meithhad text, as a whole, has strong over-tones of fear-mongering. It is meant to convince a woman reader to forgo marriage with a human man and instead marry Christ. The pathetic element does not deny the practical realities that most of these women would have faced when they considered marriage or a vow of celibacy. I have included a large selection of text from the Hali Meithhadbelow with their translations from the TEAMS site:

(1) Of thes threo hat (meithhad ant widewehad, ant wedlac is the thridde) thu maht, bi the degrez of hare blisse, icnawen hwuch ant bi hu muchel the an passeth the othre. (2) For wedlac haveth frut thrittifald in Heovene, widewehad sixtifald. (3) Meithhad, with hundretfald, overgeath bathe. (4) Loke thenne herbi, hwa se of hire meithhad lihteth into wedlac, bi hu monie degréz ha falleth dunewardes; ha is an hundret degréz ihehet towart Heovene hwil ha meithhad halt, as the frut preoveth, ant leapeth into wedlac — thet is, dun neother to the thrittuthe — over thrie twenti ant yet ma bi tene. (5) Nis this, ed en cherre, a muche lupe dunewart? (6) Ant tah, hit is to tholien ant Godd haveth ilahet hit (as ich ear seide) leste, hwa se leope ant ther ne edstode lanhure, nawt nere thet kepte him ant drive adun swirevorth withuten ike|punge deope into Helle. (7) Of theos nis nawt to speokene, for ha beoth iscrippet ut of lives writ in Heovene. (Stanza 17)

(1) Of these three states (maidenhood and widowhood, and wedlock is the third) you may, by the degrees of their bliss, know what and by how much the one surpasses the others. (2) For wedlock has a thirty-fold fruit in Heaven, widowhood sixty-fold. (3) Maidenhood, with a hundred-fold, surpasses both. (4) See then by this: whoever descends into wedlock from her maidenhood, by how many degrees she falls downwards; she is lifted toward Heaven one hundred degrees while she keeps her maidenhood, as the fruit proves, and she leaps into wedlock — that is, down lower to the thirtieth — over three twenties and yet more by ten. (5) Is this not, at one time, a great leap downward? (6) And yet, it is to be endured and God has decreed it (as I said before) since if anyone who leapt and did not stop there at least, there would be nothing nearby that would catch him, and he would fall downward headlong without protection deep into Hell.[11] (7) Of these ones there is nothing to say for they are scraped out of the book of life in Heaven. (Stanza 17)

(1) Thus, wummon — yef thu havest were efter thi wil, ant wunne ba of worldes weole — the schal nede itiden. (2) Ant hwet yef ha beoth the wone, thet tu nabbe thi wil with him ne weole nowther, ant schalt grevin godles inwith westi wahes, ant te breades wone brede thi bearn-team, ant teke this, liggen under la|thest mon, thet, thah thu hefdest alle weole, he went hit te to weane? (3) For beo hit nu thet te beo richedom rive, ant tine wide wahes wlonke ant weolefule, ant habbe monie under the hirdmen in halle, ant ti were beo the wrath, other iwurthe the lath swa thet inker either heasci with other — hwet worltlich weole mei beo the wunne? (4) Hwen he bith ute havest ayein his cume sar care ant eie. (5) Hwil he bith et hame alle thine wide wanes thuncheth the to nearewe. (6) His lokunge on ageasteth the. (7) His ladliche nurth ant his untohe bere maketh the to agrisen. (8) Chit te ant cheoweth the ant scheomeliche schent te; tuketh the to bismere as huler his hore; beateth the ant busteth the as his ibohte threl ant his ethele theowe. (9) Thine banes aketh the ant ti flesch smeorteth the, thin heorte withinne the swelleth of sar grome ant ti neb utewith tendreth ut of teone. (10) Hwuch shal beo the sompnunge bituhen ow i bedde? (11) Me theo the best luvieth ham tobeoreth ofte thrin, thah ha na semblant ne makien ine marhen, ant ofte of moni nohtunge, ne luvien ha ham neaver swa, bitterliche bi hamseolf teonith either. (12) Heo schal his wil muchel hire unwil drehen — ne luvie ha him neaver swa wel — with muche weane ofte. (13) Alle his fulitohchipes ant his unhende gomenes, ne beon ha neaver swa with fulthe bifunden (nomeliche, i bedde), ha schal, wulle ha nulle ha, tho|lien ham alle. (Stanza 23)

(1) This, woman — if you have a husband for your desire, and happiness also in world’s joy — shall certainly happen to you. (2) And what if they are missing for you, so that you have neither your desire with him nor wealth, and will grieve impoverished within empty walls, and to lack of bread breed your offspring, and besides this, will lie under the most loathsome man, who, though you had every kind of wealth, he turns it into suffering? (3) For suppose now that for you riches are plen- tiful, and your wide walls proud and prosperous, and you have many servants under you in hall, and yet your husband is angry with you, or becomes loathsome to you so that either of you both are angry with the other — what worldly wealth may be a joy to you? (4) When he is out you have terrible anxiety and dread about his return. (5) While he is at home all your wide walls seem to you too narrow. (6) His gazing on you frightens you. (7) His loathly noise and his wanton uproar make you frightened. (8) He chides you and nags you and shamefully disgraces you, ill- treats you insultingly as a lecher does his whore, beats you and buffers you as his purchased thrall and his born slave. (9) Your bones ache and your flesh smarts, your heart within you swells from bitter anger and on the outside your face burns with rage. (10) What will the joining between you in bed be like? (11) Even those who love each other best often quarrel in there, though they do not show it in the morning, and often, however well they love each other, they bitterly irritate each other over many nothings when they are by themselves. (12) She must endure his will greatly against her will — however much she loves him — often with great misery. (13) All his foulnesses and his indecent love play however filled with filth they may be (in bed, that is!), she must, will she nill she, endure them all. (Stanza 23)

(1) Crist schilde euch meiden to freinin other to wilnin forte witen hwucche ha beon, for theo the fondith ham meast ifindeth ham forcuthest, ant cleopieth ham selie iwiss the nuten neaver hwet hit is, ant heatieth thet ha hantith. (2) Ah hwa se lith i leifen deope bisuncken, thah him thunche uvel throf, he ne schal nawt up acoverin hwen he walde. (3) Bisih the, seli wummon: beo the cnotte icnut eanes of wedlac, beo he cangun other crupel, beo he hwuch se he eaver beo, thu most to him halden. (Stanza 24)

(1) May Christ shield every maiden against asking or wanting to know what they are, for those who experience them the most find them the most hateful, and they call those blessed indeed who never know what they are, and hate those who practice it. (2) But whoever lies deeply sunk in the swamp will not rise out of it when he wants to, though it seems wretched. (3) Look, blessed woman: once the knot of wedlock is knotted, be he idiot or cripple, be he what so ever he may be, you must stay with him. (Stanza 24)

I want to preface my next comments and say that I am a fan of The Katherine Group as a series of texts. I do appreciate the style and craftsmanship with which the compositions were put together. I keep returning to them. However, as interesting as The Katherine Group is to study, the Hali Meithhad selections do not speak as a text that was trying to sincerely help women. The text indicates a number of frightening or at least upsetting scenarios, in which a woman would have to choose between two difficult and unenviable lives: possible safety and security in a cloister or freedom in the world with a terrifying, unsecure man. The way the author presented the options, it was indeed a Sophie’s Choice. If Hali Meithhad had women’s best interests at heart, it might have provided alternative choices or even investigated why the Church only provided those two options for a good life that would lead, potentially and hopefully, to heaven.

However, the male author of Hali Meithhad understood his writing prompt. The author may have simply been trying to bolster the population of nuns at the monastery by producing a propaganda piece, which was not an unusual practice.[12] Additionally, as Stanza 24.4 states, “Look, blessed woman: once the knot of wedlock is knotted, be he idiot or cripple, be he what so ever he may be, you must stay with him.” The author of this text fully understood the realities of a woman’s world. The Church did not provide an “out” for women from marriage, even if it clearly understood––and acknowledged at length in satire[13] and religious texts––the dangers of a bad marriage. The Church knew what kind of life it often damned women to.

As Hali Meithhad further states in Stanza 17.6, “And yet, it is to be endured and God has decreed it (as I said before) since if anyone who leapt and did not stop there at least, there would be nothing nearby that would catch him, and he would fall downward headlong without protection deep into Hell.” This line indicates that marriage was meant to “catch” sinners before they sinned even more deeply; in this way, the wives ought to catch their husbands’ sins and endure them.[14] Instead of proposing a real solution (to the problem that it had created), the Church suggested that women take a vow of celibacy before marriage or after widowhood. Since the women who dedicated themselves to monastic vows often signed over their property, loyalty, bodies, and souls to the Church at this time, Rome had no reason to reform their marriage laws to allow for divorce. It was the ultimate power move.

Okay, so this is a mess. Do we have any proof that women wrote about themselves?????? What did they do about all of this?

YES. Women wrote about themselves quite differently than men did, to be honest. When we look at the works of Julian of Norwich’s The Showings of Divine Love and The Book of Margery Kempe, which were both written directly by or dictated in person by women, what we see about the minds and thoughts of women transgresses the neat little compartments that the Church and society wished to categorize women into. Women were quite aware that they were written about negatively, and it shows up in their work (there are multiple instances in which Margery Kempe reacts to misogyny and threats of being burnt). However, literate and engaged women were not defined by these acts of oppression, and their literary and spiritual activities far exceeded the parameters set by works like Hali Meithhad.

For example, Margery Kempe is just funny. She is absolutely hilarious. She is also tragic, poignant, and very fully human. With that in mind, I will try to do the complexity of her work justice below.[15]

As a quick background, Margery Kempe (c. 1373-14738) was born and lived in King’s Lynn, England, to parents who were part of the merchant class. She married John Kempe at around twenty years old. After she gave birth to her first child, she suffered serious hallucinations of devils and demons for eight months. She called to her confessor to confess a grave sin out of fear of being damned to hell. She continued to be oppressed by visions of “devlys opyn her mowthys al inflaumyd with breny[n]g lowys of fyr” (devils opened their mouths with burning flames of fire” (Book of Margery Kempe, l. 201). The devils threatened her and coaxed her into slandering her family and faith; Margery became so violent she had to be restrained. She was “owt of hir mende.”[16]

This event set the stage for Margery’s mystical journey. She went on to have at least fourteen children (who do not particularly appear in her Book, though “motherhood” is a very strong thematic element). The Book of Margery Kempe, we believe to be dictated by Margery herself through two scribal processes, records her visions, mystical experiences, travels, and her attempts to gain religious recognition in England and abroad for her visions. She notes her conversations with Bishops, Archbishops, and confessors, as well as the threats she received in public for the visions she received, which often moved her to explosive tears which disturbed the public. She received pressure for her interactive visions with Jesus and the Virgin Mary. In her visions, Margery saw and spoke-to-and-with Jesus as her lover, her savior, or a babe in arms. She saw and interacted with Mary as a mother cradling a child, and she gave succor to Mary as she mourned the death of her son.

Margery was living and writing within the mystical tradition, so she was by far not the only woman who experienced these visions (for example, Julian of Norwich, Hildeburg of Bingen, Catherine of Siena). The mystical tradition was not limited to women, though many who experienced and wrote down their visions were women. The tradition became associated with Lollardy, which came under pressure by the Church as a form of critique and democratic, individual religiosity (so, heresy). However, Margery was not a Lollard as far as we can tell. She appealed to the Church to be accepted as orthodox.

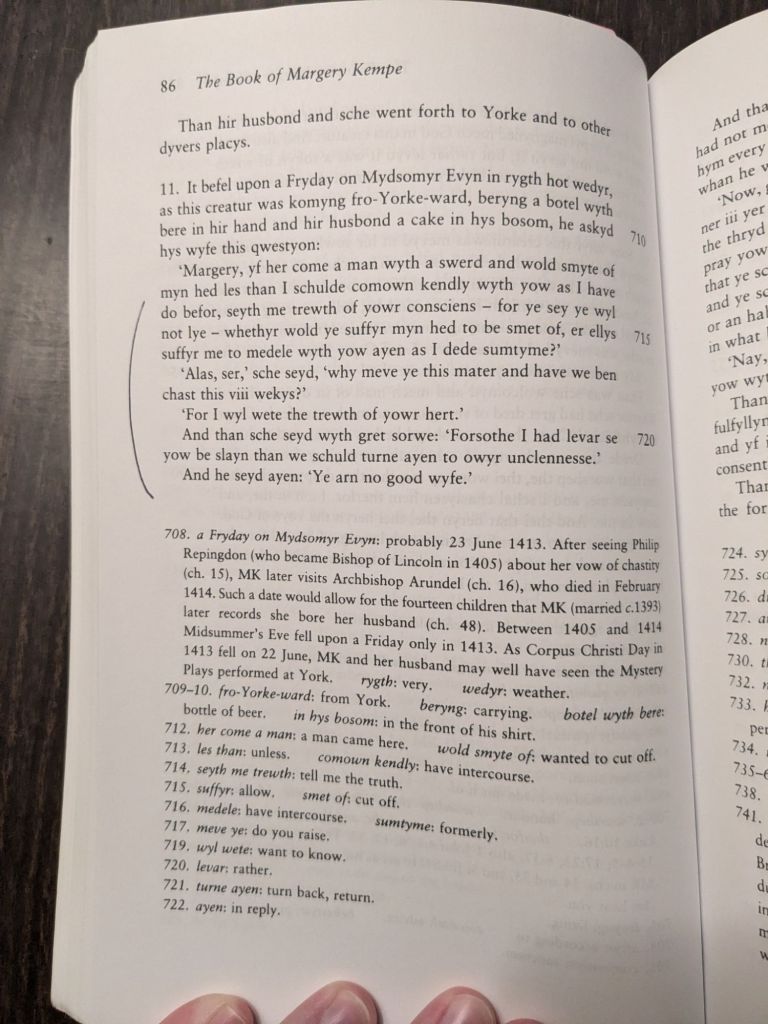

That is to say, Margery is complicated. There is a lot to her story. The male author of Hali Meithhad presents a woman reader with the choice between a terrible, horrible husband and life in a monastery[17]. In that profile, women are flat characters with no agency. However, Margery is nuanced and creative. Look at the interchange she shares with her husband John below:[18]

Translation:

‘Margery, if there came a man with a sword and [he] would smite off my head unless I should have intercourse with you as I have before, tell me the truth––you you say you will not lie––whether you would prefer my head to be cut off, or else suffer me to have intercourse with you have I have formerly?”

“Alas, sir,” she said, “why do you raise this matter when we have been chaste for eight weeks?”

“For I want to know the truth of your heart.”

And then she said with great sorrow. “Surely, I had rather see you be slain than we should be turned against our[19] uncleanness.”

And he said in reply: “You are no good wife.”

Margery does something clever here. At this point in the text, she has already given her husband John at least fourteen children. In the interchange above, Margery was pursuing a new state of chastity after marriage and childbirth because of a series of visions she had, in which Christ had promised her a new state of holiness if she dedicated herself to him. In this dedication, she would not be required to join an order of nuns, but she needed to remove herself from her marital bed and pursue a personal, sacred vow.

As can be seen above, her husband was not particularly pleased with this arrangement and gives her an ultimatum: would you rather have sex with me or see me dead? Margery remarks that she would rather see their souls clean than to see him alive. John huffs. Ultimately, Margery strikes a bargain with her husband. The Book of Margery Kempe records that John admitted he had left her alone for the last eight weeks out of fear (he had witnessed the power of her visions, and apparently believed in her spiritual connection enough to be afraid of God if he touched her). John said he would leave her alone if she would still lie in bed with him, join him for meals on Friday, and pay off all his debts. After a brief tête-à-tête with God, she agreed.[20] By these terms, Margery gained what could be considered her bodily and spiritual freedom through her own agency.

The example in The Book of Margery Kempe is very significant because it shows much more credibly how women interacted with the state of marriage and vows of celibacy. Margery was married and a mother, but that was not the end-point to her very rich life experiences. In her interaction with John above, she breaks the parameters of the life that had been set for her and finds a new option. Often male authors write about women in the abstract, as strange beings who could cause spiritual harm through accidental exposure. However, the selection from Margery is grounded in the practical. She accepts the situation of her state and then barters her way out of it in the most pragmatic, business-like terms, using the context of her spiritual visions. She is not crazy but really quite astute.

Most interestingly, Margery does not rely upon the established norms which, as Hali Meithhad states, make it necessary for a woman to turn to a husband or security in the cloister. Her creative resolution involves living the social life of a married woman (this would guarantee her social, physical, and economic freedom) but only by taking a vow of celibacy within marriage (this guarantees her bodily and spiritual freedom). Her vow of celibacy is interesting because it is predicated on a vision she had of Christ, who promised her a new chastity, after marriage and childbirth. On some level, Margery quite literally tosses out the idea of virginity, which the Church had used by that time to control the bodies of women and their activities for more than a millennia.

On some level, Margery quite literally tosses out the idea of virginity, which the Church had used by that time to control the bodies of women and their activities for more than a millennia.

In this way, I think it makes more sense to listen and read women’s writings as more credible than we read the writings of contemporary men when women are the object of description. The male authors who describe women do so with a great deal of bias, and that bias is meant specifically to enact control. We should not count male authors as more believable. Nor should we seek out their sources first when gathering evidence. In many cases, male authors may have had little contact with women that they would have viewed in evolved terms. Classical, Medieval, Early Modern, Renaissance, Enlightenment, and even Victorian scholars are consistently discovering the existence of more women authors who have impacted their literary fields.

The suggestion to listen and read from women is not at all new––it has strong precedents in Feminism, Queer Studies, African Studies, and Subaltern Studies––but personal and scholarly habit requires us to reach out to a full constellation of authors. In the end, the women authors we have found are once again drowned out by their contemporaries who add “context.” That context can take away or even bury again what they were trying to say, since value is not placed in marginal voices.

Therefore, it is time that readers just STOP reading the works of men, first or even only, to understand women. The works of women are right there. Just read them.

[1] I’m not saying that I think bigamy is a good idea, but this is to open up our understanding of history.

[2] Stephanie. Anglo-Saxon Women and the Church: Sharing a Common Fate. The Boydell Press, 1992., pp. 46-61.

[3] Mayr-Harting, Henry. The Coming of Christianity to Anglo-Saxon England. Fabic of British History. B. T. Batsford, 1972. Pp. 248-250.

[4] Hollis, pp. 80.

[5] Love ya Erasmus, but you didn’t have to do that.

[6] Aelfric, Mary Clayton, and Juliet Mullins. Old English Lives of Saints. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2019. Pp. 219-237, 125-153.

[7] Ælfric is the president of the medieval He-Man-Woman-Hater’s Club.

[8] Lochrie, Karma. Margery Kempe: Translations of the Flesh. Pp. 5, 16-17, 19-20, 23.

[9] See the Sawles Warde in the Katherine Group.

[10] https://d.lib.rochester.edu/teams/text/huber-robertson-the-katherine-group-introduction

[11] Basically, marriage is meant to “catch” sinners before they sin even more.

[12] See “Edith’s Choice,” by Katherine O’Brien O’Keefe in Latin Learning and English Lore. The essay discusses how Goscelin Saint-Bertin wrote that the child Edith chose the Wilton monastery by divine destiny. Edith was described to have made her own choice rather than to have been committed by her parents. O’Brien O’Keefe contextualizes the essay amid concerns like parental oblation, the Norman invasion, the growing wealth of the church, and the indissoluble act of veiling as a form of taking a vow.

[13] Erasmus’ In Praise of Folly

[14] But “at least they have a husband,” right?

[15] Scholars sometimes indicate that we should address Margery Kempe as a literary character since we are not sure about her historicity. I want to push back here. We have so comparatively few works by women. If we detract from her credibility ourselves, then we are participating in the same misogyny that makes it difficult for women to be read in the first place.

[16] “Owt of her mende.” Line 199. Barry Windeat references Atkinson 1983: 209, which speculates that Margery was suffering from post-partum psychosis.

[17] Life in a monastery may not as bad as the modern, public perception; however, if those are the only two choices, I am sure any woman would want more options.

[18] Barry Windeat, ed. Book of Margery Kempe: Annotated Edition. Library of Medieval Women.2006. pp.86.

[19] I do not have the English translation of The Book of Margery Kempe on hand. The owyr here appears to indicate a first-person plural possessive pronoun, which means it would be translated as “our.” Harvard’s Geoffrey Chaucer Website, Lesson 5, Chaucer’s Grammar (https://chaucer.fas.harvard.edu/lesson-5), indicates that “oure” is the first-person plural possessive. Because of the spelling change in Margery Kempe, which may be dialectical, I am not sure of this translation, but if I am informed otherwise, I will certainly update this!

[20] Lines 723-784.

Leave a comment