This post is part of a series. If you would like to read the first post and access the full list in the series, please follow this link: On the Synod on Synodality: Part I.

The last post in this series, St Wilfrid and How Rome Came to Britain: Structure, Contention, and Conflict, explored the background of the debate about Easter and the lines of argument drawn by the Celtic and Roman ecclesiastics in Britain during the eight century. The post considered the premise that contemporary Roman Catholic structure is a modern concept, which has been under negotiation and constant revision for millennia. As part of this negotiation, St Wilfrid’s appeals to the authority of the Vatican helped to seal Roman dominance in the British Isles.

In medieval texts, the figures mentioned and the space given to them by an author can indicate some sense of their popularity. Conversely, those omitted from a narrative or given less space can indicate less positive attention on the part of the author. The same could be said about St Wilfrid, about whom multiple references exist by his contemporaries.

As Bertram Colgrave remarks at the beginning of his edition on The Life of St Wilfrid, “It is clear through [the Venerable Bede’s] account that he is not altogether favourable to Wilfrid. . . he describes only one miracle connected with Wilfrid. . . .”1 In contrast, the first extant Life of Wilfrid was written by its possible author, Eddius Stephanus, a disciple of Wilfrid, is more positive, but so much so that it has been said to be “credulous and partisan.”2 I am not sure if I agree with Colgrave’s assessment of Bede, but it is worth keeping in mind.

Wilfrid stands as a controversial character in British history. While enormously influential, he was repeatedly exiled and imprisoned. He had a habit for crossing his fellow countrymen and flouting local politics by appealing to Rome, which in effect contributed to his broad influence and, ultimately, his misfortunes.

During the debate on Easter (see the last post in this series above for more details), St Wilfrid defended the Roman ecclesiastical system in England. At this point, he was closely allied with Aldfrith of Northumbria, who granted him a monastery at Ripon and under whose influence he was ordained as a priest by Bishop Agilberht.3 According to Stephanus, Wilfrid was elected to the bishopric of York after the debate over the dating of Easter. However, he refused to be ordained by a Quartodeciman (or a dissenting Celtic), who he considered to be out of communion, since such dissenters still followed the Easter date and were not under the authority of the Apostolic See. He requested to be sent to Gaul receive his ordination as a bishop properly.4

Wilfrid’s blatant disregard for the authority of his British peers ruffled a few feathers. Wilfrid’s expedient return to York was delayed after his ship was cast ashore among the South Saxons on the return voyage. As Stephanus tells it, Wilfrid and his retinue escaped a horde of pagans and then made their way back to York. In the meantime, King Oswiu (Aldfrith’s father) installed Bishop Chad of Ireland to the See of York. (Stephanus here is intentional to point out that Chad is an admirable man and that the decision had been made in error). However, Chad remained as bishop of York, so Wilfrid had to return as abbot of his previous monastery in Ripon.5

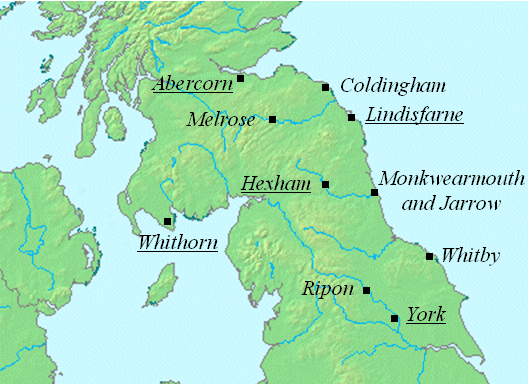

There are a lot of names in this post, so here is a handy guide!

After three years, Archbishop Theodore removed Chad from the See of York and re-installed Wilfrid as bishop. The text here is imbued with passion against the Quartodecimans, as it describes Chad’s penance for taking over another’s rightful place.6 Stephanus describes Wilfrid’s astute restoration efforts for the churches at Ripon, York, and Hexham as well as his miracles (such as restoring a child to life and healed a boy whose bones had been entirely broken in a fall).7

From this point, Wilfrid entered multiple periods of exile after he was deprived of his bishopric. Wilfrid personally appealed his case to Rome three times. The descriptions of trials according to Bede and Eddius Stephanus differ widely, which can tell us how contemporary authors read him according to their religious and political biases.

First Trial and Exile

In his first exile, Stephanus attributes his removal to the court stratagems of King Ecgfrith of Northumbria, particularly his queen Iurminburg, who riled her husband up to envy with stories of Wilfrid’s riches (see endnote).8 Wilfrid was told by Archbishop Theodore that his lands would be seized; Stephanus indicates here that no reason was given other than the lands had to be taken. Wilfrid left England secretly and traveled to Rome to appeal to the Apostolic See under Pope Agatho. There he found that Archbishop Theodore had already sent on letters through the monk Coenwald describing the British account.

After examining the case, Andrew, Bishop of Ostia, and John, Bishop of Porto, stated:

“In these letters, though they introduce many doubtful points, we find that he has not been convicted of any crimes in accordance with the plain sense of the sacred canons, and therefore his ejection is not canonical, nor have his accusers been able to prove by their own statements that he had been guilty of any crimes whatsoever, the scandal of which would justify his degradation. But on the contrary we would consider that it was moderation which kept him from mixing himself up in certain seditious strife.”9

Pope Agatho confirmed that Wilfrid did well to seek the canonical aid of Rome, rather than responding in kind to his adversaries in Britain. The synod further replied that Wilfrid should receive back his previous bishopric, with the current interlopers driven out. Those who deprived Wilfrid of his place could be removed from their position (if clerical) or excommunicated.10

Wilfrid was bishop of Hexham, Ripon, and York, which is geographically a massive area. (Wikipedia)

However, the authority of the Holy See was not customary in Britain at this early juncture. When Wilfrid returned with the Papal bull, Ecgfrith refused to heed it and instead put Wilfrid into prison, ultimately placing him into solitary confinement, refusing visitors to him, and disbursing all his possessions, including a holy reliquary which Iurminburg wore around her neck sacrilegiously. According to Stephanus, the Northumbrian court considered that the Vatican’s decision had been biased towards those loyal to its own See and that Wilfrid had “bought [his bishopric] for a price.”1111 Wilfrid remained in prison until the Abbess Æbbe interceded: when Queen Iurminburg was suddenly struck ill and dying, Æbbe said the reliquary must be returned and Wilfrid set free. In the manner of early miracle stories, Queen Iurminburg was healed, and Wilfrid was released.12

From this point, Wilfrid began a period of wandering. He attempted to stay in the court of Mercia with the kingdom’s reeve, but the queen there was the sister of Ecfrith. He fled to West Saxony, where he stayed some time, until he was driven out again, because the Queen Centwini was sister to Iurminburg.13 (It should be noted that the dynasties of early English and Celtic kingdoms were just as complicated and fraught as their modern corollaries, and memory was certainly long.) Stephanus describes that everywhere Wilfrid wandered, he was persecuted and found no rest. Finally, Wilfrid, entered the land of Sussex, which had not yet been evangelized. After telling King Aithilwalh his story, they formed a peace treaty together which enabled Wilfrid to dwell in Sussex, preach, and to establish a cloister.14

After several years, Caedwalla became king of West Saxony, at which time he brought Wilfrid on as friend and holy father. Soon after Caedwalla successfully solidified his kingdom and quite evidently became a major political player, the Archbishop Theodore invited Wilfrid to London to make peace before he died, during which he apologized for denying Wilfrid of his possessions for no fault (see endnote).15

When King Ecgfrith was killed in battle, Aldfrith took over Northumbria and restored Wilfrid to his previous bishopric. For several years, they lived in great peace. Stephanus indicates that the king and Wilfrid began to argue over the original feud. That is, the monastery and churches had been deprived of their territories by the king, and so the lands were no longer independent and self-sustaining. Most significantly, Wilfrid and the bishopric were required to follow the decrees of Archbishop Theodore which contradicted those of Rome.16

An engraving of a painting from 1519 in which Cædwalla grants Wilfrid land at Selsey (Wikipedia).

At this point, King Aldfrith hosted the Atwinsapathe Council, where the issue of Apostolic versus local authority reached a critical flexion. The theme of this section emphasizes the petty resistance to Apostolic decree and the papal authority, while it highlights Wilfrid’s acceptance of and easy use of canon law. In a moment of high drama, Wilfrid received a midnight visitor who warned him that the bishops intended to trick him into signing away his lands and bishoprics through a technicality. When Wilfrid returned to the council the next morning, he took the advice of the spy and refused to sign or submit to any synodal decision unless the archbishop indicated that it was in accord with the holy fathers. Stephanus relates that his peers realized the jig was up; they said they would strip him of his rank and take his possessions anyway, but that they would at least leave him his first monastery at Ripon out of some humanity.17

With this, Wilfrid once again appealed to the authority of Rome to settle the matter.

Second Trial in Rome

Wilfrid arrived in Rome to present his case before Pope John VI, while the Archbishop Berhtwald sent letters supporting the British charges. Wilfrid submitted his petition, citing the decisions of their predecessors (ie Pope Agatho, with correspondence from Popes Benedict and Sergius), as he put himself under the authority of Rome to determine whether he ought to govern the bishoprics of Ripon, Hexham, and York. In response to Wilfrid’s petition, Pope John VI re-opened the case that had previously been brought so that the Apostolic See could examine all those papers while they considered the current state of affairs.18

In the court, the archbishop’s messengers were the first to speak, accusing Wilfrid of refusing to obey the archbishop’s decrees. Stephanus writes that Wilfrid, now bent over with age, answered that he could in no good faith obey the archbishop, since the cleric wished him to fulfill a promise without revealing the scope of his request. After the accusers and supplicant spoke, the Apostolic See conferred among themselves in Greek. They explained that their rules did not allow them to consider further accusations against a cleric if the first charge was not proven, but to settle the matter entirely, they would go through all the records of the accusation thorough.

Therefore, after four months and seventy sittings of cross-examinations, Wilfrid was declared innocent of all crimes.19

Wilfrid wished to stay in Rome to live out the rest of his old age; however, he was ordered to return to Britain by the Holy See. The Synod produced a document of protection for him. The bull summarized the main actors and issues of the original case, stating that the concerns were resolved with all but the few who were still angry. These current concerns were fully examined, taking into account previous evidence, and Apostlic See found Wilfrid innocent. The Apostolic See commanded Archbishop Berthwald to host a synod to resolve its issues, under a sacred threat.20

From this point forward, the Life of Wilfrid reaches its denouement. Wilfrid returned to his bishopric in Ripon. More could be said about his final years––he was visited by the angel Michael, for example, which is cool––but for the purposes of this writing, his long and arduous travels were at an end. He lived for several years in peace and then passed away of a sickness.

Bede’s Account

Bede includes a brief vita for Wilfrid (Bede V.XIX). The brevity of the text certainly omits certain details and important characters. Bede’s style summarizes the events so that they appear compressed and flat. In comparison, Stephanus wrote with a zealous indignity at the mistreatment of his mentor, so that the tragedy and pathos of Wilfrid’s time in exile and prison could be felt by the reader. Stephanus’s account is dramatic, evocative: we might even become angry on the behalf of Wilfrid. However, Bede’s version minimizes these experiences so that Wilfrid’s inner life could be read as indifferent. His difficult experiences simply become steps on the path towards his own sainthood as he defends England’s loyalty to orthodoxy and Rome. In the hagiographic style, Bede minimizes Wilfrid’s distaste for pain, since saints tended to relish martyrdom.

While Stephanus very clearly details Wilfrid’s troubles, Bede is less clear. He does not clearly state why Wilfrid was disinvested or accused by his peers. Rather, a reader must rely upon inference to understand the context.

In the vita, Bede indicated an issue that lingered after of the Easter Debate (an oft-repeated theme in Bede):

. . . he won the friendship of King Alchfrid, who had learnt to follow always and love the catholic rules of the Church; and therefore finding him to be a Catholic, he gave him presently land of ten families at the place called Stanford; and not long after, the monastery, with land of thirty families, at the place called Inhrypum [Ripon]; which place he had formerly given to those that followed the doctrine of the Scots, to build a monastery there. But, forasmuch as they afterwards, being given the choice, had rather quit the place than adopt the Catholic Easter and other canonical rites, according to the custom of the Roman Apostolic Church. . .21

and

At the same time, by the said king’s command, he was ordained priest in the same monastery, by Agilbert, bishop of the Gewissae above-mentioned, the king being desirous that a man of so much learning and piety should attend him constantly as his special priest and teacher; and not long after, when the Scottish sect had been exposed and banished, as was said above, he, with the advice and consent of his father Oswy, sent him into Gaul, to be consecrated as his bishop. . .22

However, Bede gives no specific reason for Wilfrid’s accusations. He indicates only that “in the reign of Egfrid, [Wilfrid] was expelled from his bishopric”23 as a direct cause for his disinvestment and plea to Rome. According to Bede’s timeline, the Scottish sect (or Celtic Quartodecimans, as mentioned in the last post) had already been “exposed and banished.” Land rights were contentious in this period, since monastic holdings were new. Ecclesiastical holdings would have been granted by a king to a specific family member of religious persuasion, who historically would have been Quartodecimans.24 In this case, Wilfrid could have been seen as usurping not only religious authority but also ancestral land claims. Likewise, Bede relates that members of these groups could vacate or be banished from their lands. However, by summarizing Wilfrid’s life so succinctly, Bede neglects to provide the context that would clarify why Wilfrid’s enemies were so aroused by his claims to orthodoxy and Roman authority.

That is, Bede never clarifies the details of the accusations against Wilfrid. In fact, he relates that Wilfrid’s enemies made false charges against him which forced him out of his bishopric once he regained it. However, Bede never provided details about the content of these details. He spends far more time discussing Wilfrid’s holiness and good character as well as his acquittal in Rome. At the end of the vita, Bede recounts Wilfrid as the bishop who returned the true faith to the British Isles under the authority of the Roman Church.24

I wonder if Bede de-emphasized the particulars of Wilfrid’s trials intentionally. While he was writing about Wilfrid, he was writing about Wilfrid the saint, who was more of an image than a fully fleshed person. The Ecclesiastical History of the English Church by Bede is not without its scandals or intrigue (by far! pop some popcorn!), but the purpose of the text is to put the figures into the larger context of the bend of an optimistic Christian narrative. Since many of the facts of Wilfrid’s trials indicated in-fighting and schism, Bede did not omit as much as skirt around the pith of the story.

For that, we may just have to read Stephanus. With, perhaps, a grain of salt.

Conclusion

St. Wilfrid is important in the history of Britain and the Church as a Roman institution because without Wilfrid, the mish-mashed gathering that became “the Church” might not have become Roman in England until much later. Because of Wilfrid’s own misfortunes, he forced a reckoning of local with Papal authority that resulted in the standardization of British church practice. He prompted England to follow Roman procedure by appealing constantly to the Pope rather than sorting issues out on a regional level.

According to Eddius Stephanus, the See of Rome found him innocent of all charges brought against him. After scrupulous review of the records and a trial which involved Wilfrid and witnesses from the kingdoms of Britain, each appeal found him guilty of no more than bad circumstances: wrong person, wrong place, wrong time.

In comparison, Bede speaks about Wilfrid as a saint. He mentions that he traveled to Rome and was acquitted, but he does not mention the issues at stake or Wilfrid’s agonies, so the reader is left to imagine the significance of the accusation. Through Bede, Wilfrid is deserving, even brave.

Eddius Stephanus addressed Bede’s omissions by stating that Wilfrid did not want to return to Britain after he was found innocent out of fear of reprisal. His fellow countrymen believed that Wilfrid had “bought off” a corrupt Vatican in order to find a desired result, so he did not know what sort of reception awaited him.

However, these events occurred over a millennia ago, and much nuance has been obscured in time. To that end, this account has followed literary varieties of Wilfrid by contrasting Bede and Eddius Stephanus, which sets perspectives against one another. Such a dichotomous reading tempts us to ally ourselves with one side or another, based upon our own sensibilities (or however we read that our modern sentiments might possibly map onto historic beliefs). In either case, both authors relate that at the end of his life he is greeted by an angel and dies in peace, which is a literary signal that he should be venerated.

Instead of investing a particular author as more truthful or trustworthy than another (that’s a dizzying exercise), I find it helpful to consider how the works of Bede and Stephanus help illuminate the changing political and religious landscape. The intrigue apparent in the early British court shows the tense relationship between the landed-ness and growing power of early monasteries. Since Christianity was still a very new religion in the seventh and eighth century, it threatened established, local power structures because of its reliance on foreign bodies like Rome, which might swallow the independence of the islands. Individual figures, like Wilfrid, help to illustrate how this process––for it was a process, which occurred over a long period of time, with a series of regressions and progressions––developed what many consider the high medieval ages.

Sources

- Colgrave, Bertram. “Introduction” Life of Wilfrid. Text, Translation, and Notes by Bertram Colgrave. Cambridge University Press, 1985. pp. xii. ↩︎

- Colgrave, xi. ↩︎

- Colgrave, Chapter VII, VIII, IX. ↩︎

- Colgrave, Chapters X-XII. ↩︎

- Colgrave, Chapters XIII, Chapters XIV. ↩︎

- Colgrave, XV. ↩︎

- Colgrave, XVI–XXIII. ↩︎

- Colgrave, XXIV. Contemporary eighth century literary texts tend to treat the political power of women queens quite neutrally. Misogynistic readings of women rulers, or the “evil queen” trope, really only began to occur from the tenth century forward along with the growing popularity of chivalric romance and the courtly love tradition. Therefore, Stephanus’ early characterization of Iurminburg as a negative inciter of male action is notable here. ↩︎

- Colgrave, XXIX, pg. 59. ↩︎

- Colgrave, XXXI–XXXII. ↩︎

- Colgrave, XXXIV. ↩︎

- Colgrave, XXXIX. ↩︎

- Colgrave, XL. ↩︎

- Colgrave, XLI. ↩︎

- Colgrave, XLII–XLIII. Stephanus does not indicate that there is a causal relationship between Caedwalla’s and Wilfrid’s friendship; however, the two sections of text are directly juxtaposed. ↩︎

- Colgrave, LXV. ↩︎

- Colgrave, LXVI–LXVII. ↩︎

- Colgrave, LI-LII. ↩︎

- Colgrave, LIII. ↩︎

- Colgrave, LIV-LIV. ↩︎

- Bede. “Book V, Chapter XIX,” Ecclesiastical History of England: A Revised Translation. Trans by John Allan Giles. London: George Bell and Sons, 1907. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- Mayr-Harting, Henry. The Coming of Christianity to Anglo-Saxon England. Fabic of British History. B. T. Batsford, 1972. pp. 18-21, 72. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

Leave a comment