Spooky season is upon us, and it is time to break out the scary skeletons! Never to disappoint, medieval manuscripts certainly bring their A-game for the creepy and crawlies. If you, dear reader, want a scare, look no further than a medieval tome!

Medieval manuscripts were composed of once-living materials, such as animals and plants. The preservation and then use of these materials in manuscript form allows them to find another life, perhaps even an undead second life.

The composition of a medieval manuscript is important here. A book was formed––in brief––from the parchment, the binding, a variety of inks, and decoration.

The binding was often made of wood, though it could be covered in leather and various decorations. Decorative elements could be impressions in the leather or metalwork. Sometimes, the binding was later restored into a reliquary (cumdach), as in the Book of Dimma. Ultimately, the binding process produced ornate and complicated pieces of art, utilizing precious metals and gemstones.

The writing surface inside the manuscript was made of parchment. Unlike modern paper, which is made of wood pulp, parchment was made of animal skins which were treated, scraped, stretched, and polished to a shine. The hair, usually from goat and sheep skins, had to be scraped, so that the parchment would become a smooth writing surface. The result was a writing surface that is more durable than modern paper, in which high quality pages (often Italian) were soft and creamy-white. The hair-side of a manuscript can be differentiated from the non-hair side because it is slightly more rough.

The contents of the manuscript could vary widely. The workhorse of text was of course ink. Usually, black ink was mixed from iron gall, which was derived from gall-nuts, which were bulbuous swellings on oak trees that occurred when wasps laid eggs in their branches (more information on the process of creating iron gall ink can be found here!). Colored ink was often derived from natural ingredients such as cochineal. The most elaborate and expensive manuscripts imported ink ingredients such as lapis lazuli to create vibrant colors. Manuscripts routinely incorporated metals as a form of additional bling. Pure white color was achieved through lead paint. In addition, gold leaf was used in abundance, from highlighting capital letters to creating entire pages of shiny, gilt copy. Some manuscripts, like the Book of Hours Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, are richly decorated. Much of the purpose of this opulence was to impress a commissioner’s fellow aristocrats.

However, medieval manuscripts invited user engagement, and a major avenue of scholarship studies how readers read, smelled, touched, rubbed, kissed, wrote into, desecrated, transported, gazed at, and altogether interacted with texts. In this way, the manuscripts ceased to be only books of study but rather they became living and embodied objects as those who interacted with them placed the manuscripts at the center of a dynamic community of learning.

Objects of study are accessed and then put away when no longer needed. They are used as references, much like a dictionary or encyclopedia. In comparison, community-centered texts can be accessed as objects of study, but they are placed within the community as figures of influence; as such, readers will engage with the text affectively and even physically react to and alter the text.

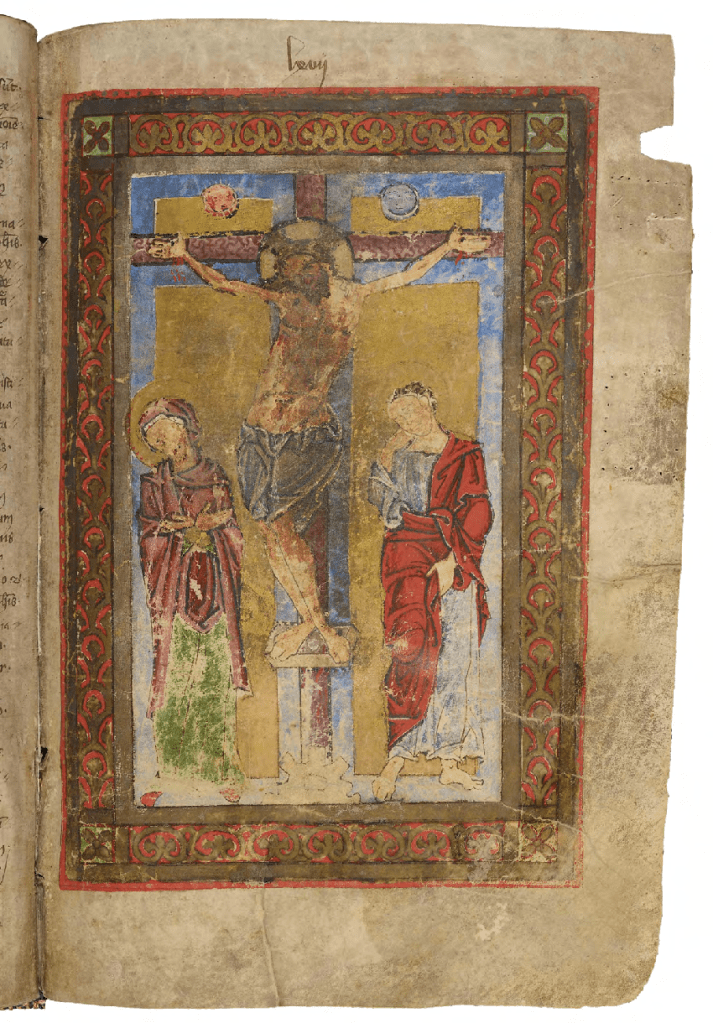

As an example of this, readers often kissed and rubbed the image of a saint as an act of devotion. According to Kathryn Rudy, much evidence exists of reader kissing, rubbing, and interacting with sacred images. Since the image of the saint stood in for the saint (that is, the image became the saint), the reader would be able to engage with the saint through the text. In this way, the manuscript was very often centered in communities (sacred and secular) as a means of affective devotion.

Crucifixion in a missal at the Canon, twelfth century with later additions, Augsburg. Oxford, Bodleian Library, Ms. Canon. Liturg. 354 fol. 67r (which is fol. Lxfij in the original foliation). From Kathryn Rudy’s Touching Parchment: How Medieval Users Rubbed, Handled, and Kissed Their Manuscripts

Therefore, manuscripts continued to have a multi-sensory use. The manuscript text can also be understood as a body because it is made of bodies that have been knit and molded into a new form. However, the medieval manuscript as body is not merely inert because it allows readers to survey the text and to engage with the emotional, personal, and even spiritual planes.

~~~~~~~As such, when we think of medieval manuscripts, lest we forget, they are not dead, they are in fact, undead. ~~~~~~~ 😮 😮 😮

And so, as it is Halloween’s Eve, always be careful what you say in front of the books!

Leave a comment